In his book The Library: An Illustrated History, Stuart Murray recalls an ominous verse written at the end of a medieval manuscript. Added in the scribe’s own hand, these lines were meant to curse anyone who might try to abscond with the sacred text:

Steal not this book my honest friend

For fear the gallows should be your end,

And when you die the Lord will say

And where’s the book you stole away?

The book in which this curse was written was most likely found in the library of a church or monastery, chained to the shelf or lectern where it rested. To whoever was its owner, it was an extremely valuable possession. To whoever might have considered stealing it, the superstitions of his era would have made such a curse quite intimidating.

Today, it seems strange to invoke the wrath of God to protect something like a book. Books are such a common item, mass produced at print shops all over the world. There are millions of them available for consumption, and they are quite affordable for the average person to collect. Any street corner bookstore sells tomes covering every subject of human knowledge, from science and mathematics to history and philosophy, and even works of fiction that appeal to the imagination, all for just a few dollars each. And with the advent of digital books and e-readers, books are more easily accessible than ever before.

It is hard to imagine a time when books were not so readily available, or so easily affordable. Nobody in the modern world would think to chain up their personal library, or to inscribe protective curses into each book. However, a mere two hundred years ago, such practices would not have seemed so unnecessary. The process of creating books has undergone dramatic changes over the past two thousand years. Today, we take them for granted. But in the medieval era, books were one of the most highly valued items, because of their content, their rarity, and the workmanship that went into their creation. In order to understand the value of books, and to be thankful for their current accessibility, their history must be traced back hundreds, even thousands of years, to the origin and development of writing itself.

“Writing has always been an essential component in the development of civilizations,” writes Marc Drogin in his book Calligraphy of the Middle Ages (11). Many ancient societies had oral traditions through which knowledge was passed down, but the spoken word was not enough to transmit the ever-growing bank of civilized knowledge as time went on. Writing originated as simple drawings on the walls of caves and buildings, meant to be a visual representation of different ideas. Gradually, these pictorial systems became complex, with hundreds of symbols to represent numerous specific ideas, as seen in Egyptian hieroglyphics and ancient Chinese writing. The transcription of information was revolutionized with the invention of the first phonetic alphabet by the Phoenicians (12) in the 11th century BC. This system was highly efficient, as it only consisted of a small set of symbols to represent the sounds of a language, rather than each individual idea. Phonetic alphabets were adopted by the Greeks, the Etruscans, and eventually the Romans. It was the Romans who would develop the alphabet still in use today, albeit with three additional letters.

Rome became the dominant power in the western world, and the empire was successful in part because of its capacity for learning. Education was a primary focus for Roman citizens, and libraries sprung up across the empire. The Roman civilization began to decline in the 4th and 5th centuries AD, due to internal crises and foreign invasions. The western half of the empire finally collapsed in 476, when a German “barbarian,” Odoacer, deposed the last emperor and declared himself King of Italy. From that point on, the once unified territories of western Europe fell into disarray. Power fell into the hands of local lords, and much of Roman culture was forgotten. The only major Roman institution that survived was the Catholic Church, which struggled to preserve peace and to protect the remnants of classical knowledge.

Europe gradually became stable again after the first two centuries of the medieval era. A new empire was established under Charlemagne, which provided a degree of unity to an otherwise divided continent. With this newfound stability, new peaceful religious communities arose. Monasteries sprung up across France, Germany and Britain. The Rule of Saint Benedict, which had been written in the mid-6th century AD, was established by Charlemagne as the standard for monastic life at the beginning of the 9th century. Benedictine rule set strict guidelines for prayer, worship, study, and work, according to Michael Kerrigan’s book Illuminated Manuscripts (13). Aside from religious facilities, monasteries often had farms, fisheries, gardens, breweries, and apothecaries, which made them an important part of the medieval communities where they were established (14-15).

Education was among the primary focuses of monastic life. In ancient Rome, children were sent to schools or taught by private tutors, and those seeking further education could travel abroad to the ancient world’s great centers of learning. After the collapse of Rome and the deterioration of its educational system, monasteries became the only schools available in western Europe (Drogin 18). Writing was one of the most important lessons taught at the monastery; nearly every scribe in the Middle Ages learned their craft at one of these religious institutions. Some remained there after their education, but others went on to work for royal courts, merchants, or whoever else might need someone capable of writing messages and keeping records (28). For those who chose to stick with the monastic life, adherence to the strict rules set forth by St. Benedict was expected. However, those who showed the greatest talent for scribal work were often relieved of other forms of labor in order to focus on their work in the scriptorium (24).

A Medieval scribe at work. Although he is pictured writing into a finished book, the pages would actually have been written before binding. From Irene O’Daly’s article “Writing the Word: Images of the Medieval Scribe at Work.”

Each new monastery needed new copies of the Bible and other books, which kept the scribes at older monasteries busy. Drogin writes, “in a world of much confusion and little learning, the dozens and then hundreds of monasteries were treasure houses of knowledge which demanded enormous amounts of writing and copying” (16-18). Regardless of its necessity, or perhaps because of it, scribal work was not easy. Kerrigan quotes one scribe’s comment in the margins of the manuscript he was copying: “Writing is excessive drudgery. It crooks your back; it dims your sight; it twists your stomach and your sides” (15). It was indeed slow, tedious work. The transcription of even a short manuscript could take weeks or months (15), but the work of the scribe, with its tedium and pain, was highly valued. Scribes were seen as giving physical reality to the spiritual treasure of the texts they copied. “The skills of the scribe were at a premium in a time before printing, when copying by hand was the only way of reproducing texts,” writes Kerrigan (15).

Because of the wealth often stored within, monasteries were prime targets for pillaging by Vikings and other foreign invaders. The scriptorium was one of the most valuable parts of the monastery, and was protected as such, often located in the safest part of the structure, where access could be blocked in case of an attack. The work of the scribes therein was simply too valuable to risk losing.

Unlike modern books, which are designed to be read as easily as possible, medieval texts were composed to be as aesthetically pleasing as possible (Drogin 20). The scribe practiced his penwork carefully, placing each stroke accurately and deliberately to create attractively uniform lines of text. A manuscript’s beauty did not end there, however. After the manuscript was written, different forms of decoration could be added. In the early Middle Ages, this decoration was generally limited to red or blue penwork, and was done by the same scribe who wrote the text (15, 26). Later, this job was taken over by a specialist known as a rubricator, who would add titles in red ink (rubrics) to the top of a page, according to the Khan Academy article, “Books in Medieval Europe.”

Most spectacular, however, was the work of the specialist known as the illuminator. Most books were largely undecorated, but those that were (primarily Bibles and other sacred texts) became highly valued works of art. The artistic trappings of religion took on great mystical significance against the bleakness of the Middle Ages. A richly illuminated manuscript, among other items of religious value, were seen “as acts of faith, not just in God but in civilization and everything it stood for” (Kerrigan 12). Illuminators vested great meaning into the colors and images they used. “Even if we do not share [the illuminated manuscript’s] religious assumptions or its social values, we cannot help recognizing and feeling nostalgic for the significance with which it invests the written word,” writes Kerrigan (27).

The process of illumination began before a page of text was written. A scribe would devise the layout in advance, often using a wax tablet to plan the design before working on the page. He would then use a ruler and a blade to mark lines for writing, a compass to draw perfect curves, and lead to sketch out pictures (Drogin 26). Once the page was prepared, the text would be written out. The style of writing depended on the region and time period in which the manuscript was created, and was limited by the tools available to the scribe. Goose quills were most often used for writing, and ink was made from either ground up soot or oak galls (Kerrigan 17). Mistakes were not uncommon, but because the writing was done on parchment (made from the skin of a calf, sheep, or goat) they could be scraped away and rewritten easily enough.

Handwritten text showing blind rules, meant to help keep the scribe’s lines straight. From “Books in Medieval Europe.”

With no centralized system of education in Europe, handwriting styles varied quite dramatically across territories of the former Roman Empire. This changed with the advent of the Carolingian Empire. Seeking to standardize documents and correspondence throughout his lands, Charlemagne initiated the development of a new universal style of writing, known as the Carolingian Minuscule (“Books in Medieval Europe”). This style was developed in a short time in the 9th and 10th centuries and saw widespread use in scriptoriums. It was not without its flaws, however. The Carolingian script was characterized by wide, rounded letters, which took up considerable space. By the 13th century, writing had gone through a slow evolution into a much more condensed form: Gothic script. Individual letters became more narrow and angular until the Textura style, known today as Blackletter, was achieved (Drogin 76-78). This style allowed much more text to be written in a smaller space, leaving extra room for illumination.

The illuminator’s work began once the text had been completed. First, gold or silver leaf was applied to the page by a thin layer of glue. It was these precious metals that led to such manuscripts being called “illuminated,” as they caused the page to shimmer with light (Kerrigan 7, 18). The drawings which had been sketched earlier were then painted with different pigments, some rare, others more common. Though scribes could not comprehend the chemical properties of these pigments as a modern person would, they were still very knowledgeable, understanding the limitations of each one, and whether two were safe to mix (18-19). To assist in their efforts, scribes often had access to model books, which contained examples of intricate capital letters, pictures of animals and monsters, and other decorations. These books could be used as a reference for certain pieces of artwork which the illuminator could not produce so well on his own (Drogin 16).

Depending on the length of the book, the whole process of writing and illuminating each page could drag on for months, or even years (“Books in Medieval Europe”). The fruits of the scribes’ labor had to be protected somehow. In the book Hand Bookbinding, Aldren A. Watson explains that in the days before bound books, papyrus scrolls were often kept in tubes for protection (9). The first books, known as codices, emerged in ancient Rome, and almost entirely replaced scrolls by the 9th century. These were made from single sheets of papyrus, hinged along the edge by lacing. According to Paul Johnson’s The Renaissance: A Short History, scribes preferred papyrus until the fall of the Rome, when supplies from Egypt became scarce. At that point, parchment (or vellum, which refers to parchment made of calf skin specifically) became more widely used. These materials were more expensive than papyrus, but also more durable. Codices, whether their pages were made of papyrus or parchment, were protected by wooden boards, which were usually covered with leather. Leather provided permanence and protection, and was receptive to decorative tooling (“Books in Medieval Europe”).

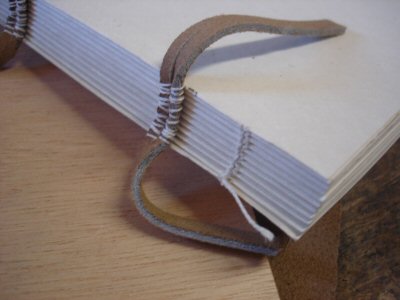

Spine of a completed text block, from Jaysen Ollerenshaw’s “An Early Gothic Bookbinding.”

As the years went on, book making became a complex art. Medieval books evolved from the simple laced codices of the Roman era to highly decorative, durable bindings. Instead of gathering blocks of individual pages, scribes began to fold pages of parchment in half to create a folio, then gathered several folios into a signature. When paper was introduced to Europe from China, it allowed new styles of folding which were not possible with the thickness of parchment. Paper could be folded twice to create a quarto, or three times to create an octavo, consisting of four and eight pages, respectively (Watson 12). These pages would be gathered into a quire, a signature of usually 24 leaves. Some scribes still preferred the luxury and durability of parchment (Kerrigan 17), but whether they chose that or paper, they used innovative new methods of binding to connect and protect the signatures. Quires were sewn together to cords or leather straps, which were threaded through holes in the boards on either side of the book block, and either pegged or glued in place. Jaysen Ollerenshaw’s web article “An Early Gothic Bookbinding” shows the steps of an elaborate 14th century binding in detail, focusing on the arrangement of leather straps, the sewing of quires, and the addition of leather over the boards.

Similar to the illuminated pages inside, the covers of medieval books became subject to intricate decorations. Members of the nobility became patrons of many different forms of art, including bookbinding; their influence on the craft of bookbinding was so great that particular bindings became known by the name of their commissioner, rather than their binder (Watson 13). Blind tooling, impressions made in leather with hot metal tools, was the most common form of decoration. Gold leaf and gemstones were included in the most elaborate bindings, and corners and clasps made of gold were common additions as well (11-13). Humanists and Bookbinders by Anthony Hobson shows detailed examples of highly decorative bindings of the late 15th and early 16th centuries, many featuring medallions and plaquettes embedded in the leather. Many of these later medieval books, instead of being written and bound by monks in a scriptorium, were done by secular craftsmen who worked by commission.

Monastic scribes were supposed to be anonymous, but it was hard for such an artisan not to take pride in their accomplishments. Some scribes would name themselves in the margins of their manuscript, or in a colophon at the end (Kerrigan 20). By the late Middle Ages, independent scribes were common throughout Europe. Some advertised themselves publicly, including Herman Strepel, a German scribe in the mid-15th century who made displays of all the different scripts he was capable of writing to attract customers. Individual bookbinders also became well-known as they worked hard to meet the increasing demand for books. Book streets emerged in major cities, where different artisans involved in book making would set up shop and compete for business. Oftentimes, a stationer would take orders for books, then hire nearby scribes, illuminators, and binders to complete his orders. In spite of the high quality of work put into these books, the profit margin was narrow. One frustrated scribe added at the end of his manuscript, “For so little money I never want to produce a book ever again!” (“Books in Medieval Europe”). A more efficient method of producing books was needed.

In the mid-15th century, a revolution began that would forever change the distribution of knowledge. Block printing had existed for many centuries, but carving the wooden blocks was as tedious as writing and illustrating by hand (Watson 12). Starting in the 1430s, an inventor and entrepreneur named Johannes Gutenberg began experimenting with a new method of printing, which he had perfected by the 1450s, according to Michael Prestwich in the book Medieval People. “The key to Gutenberg’s method of printing was the use of movable metal type” (Prestwich 266). Gutenberg developed molds for the type, a frame for it to be set in, the press itself, and new oil-based ink. His form of printing would spread rapidly across Europe, with print shops appearing all over Germany, Italy, France and Britain by the year 1500.

In his book Printing, Power, and Piety, Brad C. Pardue writes, “The introduction of printing… radically transformed the situation in Europe.” As the Renaissance and then the Reformation began, most scholars only wrote short treatises so that copies could be made easily by hand, because they depended on “literary connection to a wide audience” for their ideas to be relevant (Pardue 17). But with the new method of printing, entire books could be replicated with incredible speed. Diarmaid MacCulloch’s book The Reformation: A History states that a printer could produce 13,000 copies of a single sheet in one day (72). With books becoming more widely available, scholars could focus on reading and developing their own ideas instead of making copies of existing texts by hand (73). Printing also allowed the creation of books to be standardized, which meant the errors inherent in copying by hand were no longer present.

Printing largely made handwritten books obsolete, but scribes were still needed for large page books that would not fit on a press, or highly decorative books for wealthy clients (“Books in Medieval Europe”). Printed books also sometimes required decoration, which still had to be done by hand. The Gutenberg Bible, which was one of Gutenberg’s first major projects, was intended to look and feel exactly like a manuscript; his type was cut to resemble Gothic Textura lettering (Johnson 19), and colorful capital letters were added by an illuminator. While the necessity of scribal work dwindled somewhat, the demand for bookbinders was greater than ever before (Watson 12). Methods of bookbinding went largely unchanged until the Industrial Revolution (10), but with the advent of printing and the more widespread use of paper instead of parchment, books shifted from being large, heavy folios meant to be read on a desk to small, lightweight octavos that could be carried and read anywhere (Hobson 1).

Not only did printing influence the speed at which books could be reproduced, it led to a change in the way books were read. Gutenberg and the other early German printers sought to replicate manuscripts as closely as possible. People outside of Germany found this style of text hard to read, and began to develop their own alphabets for printing. In Italy especially, as humanist scholars looked back to the glories of Rome, printers began to use new Roman and Carolingian style typefaces, which were much easier to read than Gothic script. Perhaps the most well-known early Roman typeface was cut by Nicholas Jenson, a printer in Venice during the late 15th century (Johnson 19). The first italic typeface was cut by Aldus Manutius in 1501 as an imitation of the cursive handwriting of papal chancery, and was often used alongside Roman lettering similar to Jenson’s (19). With these new forms of lettering in printing, books were not only easier to obtain, but also easier to study.

Replica of a Gutenberg-style printing press at the Printing History Museum in Lyon, France. From Wikimedia Commons.

The ease of reproducing books through printing altered the social landscape of Europe. There had been a somewhat pessimistic attitude towards the preservation of knowledge in earlier years, due to the fragility and decay of handwritten manuscripts (MacCulloch 74). With the sudden capacity to produce books at a large scale, Europe was gripped by new optimism driven by a desire to learn. Universities sprung up, literacy rates rose, and Church funds were reallocated to schools (Pardue 19). The total number of books in Europe leapt from under one hundred thousand in 1455 to nine million in 1500 (Johnson 21). There was much more content to read, and because of how easy that content was to access, reading became a desirable skill for more people than ever before.

The Protestant Reformation may not have been possible if it was not for the advent of printing. It was the increase in the availability of Bibles that led to the Reformation, not vice-versa (MacCulloch 73). Bibles translated into vernacular languages were printed and distributed widely, allowing more people think freely about its content and to question the teachings of the Catholic Church. For leading reformers, the use of printing to distribute their writings was vital. Pardue quotes Miles Coverdale’s statement in 1555, urging Protestants to “give thanks unto God, that he hath opened unto his church the gift… of printage” (16). In 1573, John Foxe made a similar remark: “We have great cause to give thanks… for the excellent art of printing” (16). It is very unlikely that Gutenberg could ever have imagined the extent to which his invention would change the world.

Gutenberg style presses served as the standard for producing books and other printed materials up until the Industrial Revolution, when more advanced machinery was developed. Similarly, methods of bookbinding were largely unchanged until the 1800s (Watson 10). At that point in history, machine-stamped leather covers became available, but they often lacked the artistry of earlier hand-tooled bindings. Most industrial bookbinders used cheaper materials and took shortcuts in their methods to reduce costs (13-14). Just as calligraphy became a niche craft with the introduction of printing presses, fine bookbinding also turned into a rare, specialized type of work. The average consumer had little use for such finely bound texts, but some wealthy customers still appreciated not only the content, but also the workmanship of a hand-bound book.

Books today are so easy to come by, very few people take the time to consider what historical events occurred to make them such a common item. The modern world’s millions upon millions of books would never have existed if it had not been for the scribes of the Middle Ages who fought to preserve and pass down the knowledge of their time, or for Gutenberg and his contemporaries who revolutionized the process of reproducing books. The modern graphic arts industry’s deepest roots trace back to this era: unnamed monks in their scriptoriums developed the ideas of page layout, design and composition; bookbinders came up with effective and artistic means of protecting the scribes’ work; and the earliest printers set the foundations for today’s highly efficient, digitized print shops.

The mindset of the medieval person, and the value they assigned to books, is easy to understand when the history of graphic arts is considered. The act of preserving and protecting knowledge was not a task to take lightly, and scribes’ devotion to their work shows through in the sheer artistry of surviving manuscripts. Kerrigan sums up the cultural impact of illuminated manuscripts quite aptly, stating that they bore “a visual and tactile eloquence that went beyond words” (16-17). The scribe’s job was not merely to copy another person’s words, but to transcribe the very heart and soul of the society in which he lived, and to pass on civilized knowledge to the coming generations.

With the wealth of easily accessible knowledge available in the modern world, precautions such as writing curses inside books or chaining them to shelves are unnecessary, if not nonsensical. But it is thanks to the scribes and printers of the Middle Ages that such extensive literary resources exist today. Tracing the history of graphic arts, particularly the production of books, reveals many reasons to appreciate modern advancements in technology, and many reasons to be hopeful for the future of civilization.

Written February 24-March 2, 2017. Published March 4, 2017.

References

- “Books in Medieval Europe.” Khan Academy. N.p., n.d. Web. Feb. 2017.

- Carroll, Scott. Passages: 400th Anniversary of the King James Bible: Exhibition Catalog. Oklahoma City: Passages, 2011. Print.

- Drogin, Marc. Calligraphy of the Middle Ages and How to Do It. Mineola: Dover, 1998. Print.

- Hobson, Anthony. Humanists and Bookbinders: The Origins and Diffusion of the Humanistic Bookbinding 1459-1559 with a Census of Historiated Plaquette and Medallion Bindings of the Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2012. Print.

- Johnson, Paul. The Renaissance: A Short History. New York: Modern Library, 2002. Print.

- Kerrigan, Michael. Illuminated Manuscripts: Masterpieces of Art. London: Flame Tree, 2014. Print.

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid. The Reformation: A History. London: Penguin, 2005. Print.

- “Medieval Manuscripts: Bookbinding Terms, Materials, Methods, and Models.” N.p.: n.p., n.d. Traveling Scriptorium. Yale University Library, July 2013. Web. Feb. 2017.

- Murray, Stuart. The Library: An Illustrated History. New York: Skyhorse, 2009. Print.

- Ollerenshaw, Jaysen. “An Early Gothic Bookbinding.” Early Gothic Bookbinding. N.p., 2010. Web. Feb. 2017.

- Pardue, Brad C. Printing, Power, and Piety: Appeals to the Public during the Early Years of the English Reformation. Leiden: Brill, 2012. Print.

- Watson, Aldren Auld. Hand Bookbinding: A Manual of Instruction. New York: Dover Publications, 1996. Print.